Introduction

Following the resounding commercial success of the Grand Seiko Chronometer that was released to the Japanese public on December 18th 1960, and continued in production until August 1963, Seiko began work on what was ultimately to become known as the “57GS”.

The 57GS series is known by a number of names, but as we will see, it was marketed simply as the “Grand Seiko Self Dater”, so called because of the introduction of a date complication to an evolution of the original 3180 movement found in the first Grand Seiko. Based on their caseback serial numbers, production of the Grand Seiko Self Dater commenced in August 1963 - the same month that we see the final examples of the first Grand Seiko hailing from. Over the course of the production life span of the 57GS series (the final examples date from early 1968), the watches went through a series of evolutions where changes were made to the case backs (and their reference numbers), movements, dials, caseback medallions, crowns, certificates and almost certainly boxes.

The 57GS is the first Grand Seiko whose design is attributed to Taro Tanaka, and whilst initially launched with only a stainless steel case available, for the 1964 Olympics Grand Seiko introduced a variant in a solid 18K gold case, and later on, the Self Dater was made available with a gold capped case.

One of the challenges for any collector looking to add a watch from the 57GS series to their collection is that due to the relatively long production period and very rapid evolution of nuances in the physical characteristics of the Self Daters, it can be difficult when considering a particular watch to determine whether or not all aspects of the piece are “correct”. Ideally, most collectors are looking to acquire a watch that is in as close condition to how it was originally sold as possible.

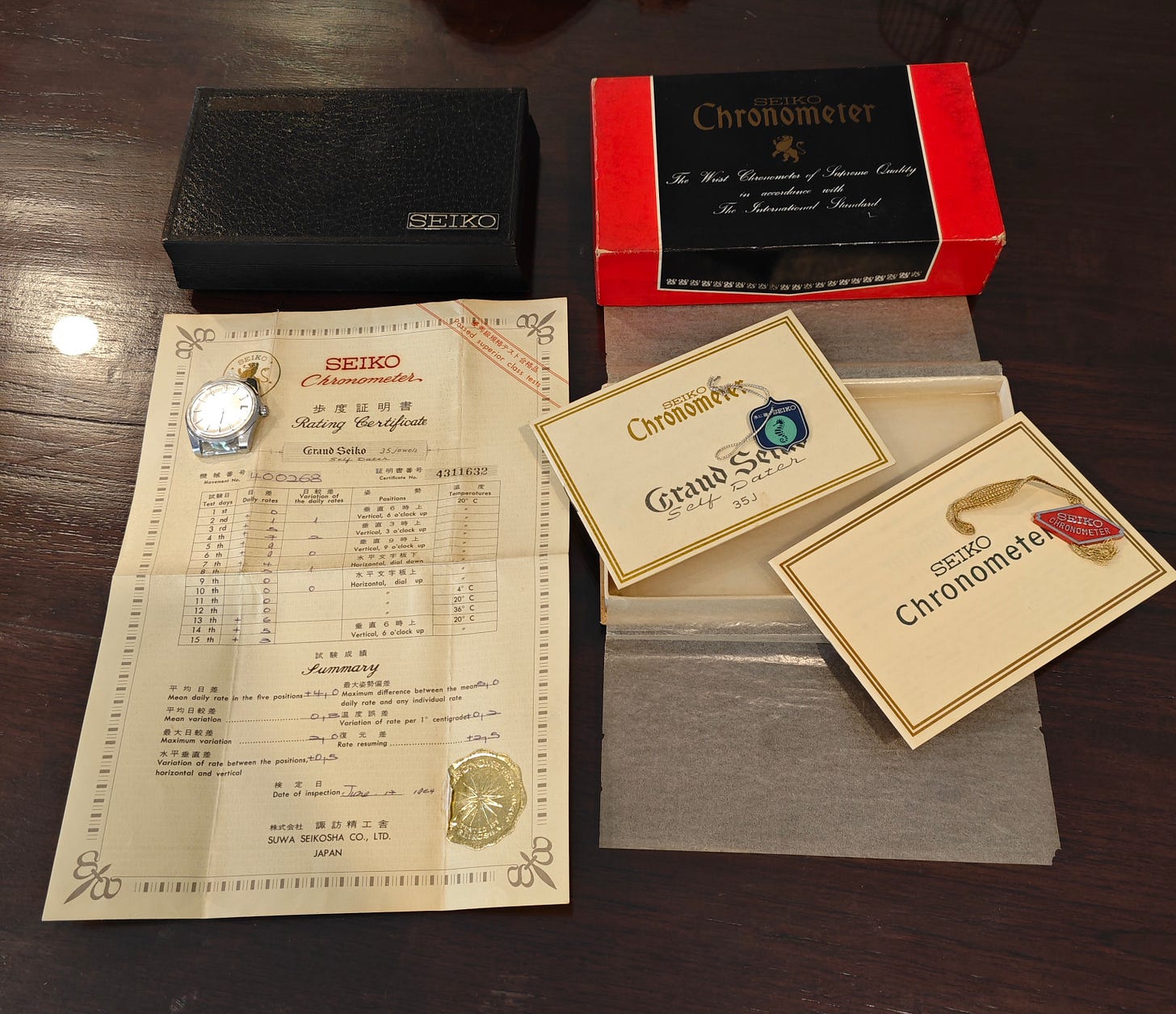

Preferably, this means finding an example similar to that shown above. If the watch is truly a “dead stock” piece that has never been on a wrist and comes complete with its original strap and buckle, and a fully intact caseback sticker, all the better.

But remember that we are talking about watches that are of the order of 60 years old now, and even finding watches just accompanied by their original certificates is a huge challenge. In the last decade, the number of examples of references from the 57GS series that have turned up on Yahoo with their original certificates is in single digits.

Even if such a set turns up, the question still remains - is everything about the watch itself original? The Self Dater was clearly made in vastly higher numbers than the first Grand Seiko, and what is also evident is that they are watches of exceptional quality - these were watches that were built to last for even more than just one lifetime. Looked after well and regularly serviced, they will probably go on forever.

And therein lies the problem - because these watches have such longevity, and because over their production lifespan so many details were changed, how, when looking at a particular example of a 57GS watch, can we know that every detail about it is “correct”.

Probably the individual with the most experience and in-depth knowledge in the world on vintage Grand Seiko would be Yoshihiko Honda, who most readers will be familiar with through his website BQ Watch. Honda-san has been dealing in vintage Grand Seiko for a number of decades now, and has written many articles over the years for the Japanese magazine Low Beat, in addition to co-writing and contributing to a number of books.

Whilst many will no doubt check his website1 on a regular basis to see what gems he has available for purchase, I rather suspect most will not have explored his site in more depth and discovered the section2 where he sets out to answer what is probably the most fundamental question when it comes to assessing the originality of a 57GS - which dials can go with which casebacks, and which dials can go with which movements?

Out of respect for Honda-san I will not reproduce here the table where he outlines what is, or might be, an acceptable combination, but instead urge you to spend some time looking at his webpage to take in what he his sharing.

From an examination of many hundreds of listings from Yahoo Japan over the years, as well as examples of watches documented elsewhere, I think I probably have enough now to go one, so let’s take a look at what unravels from all of this!

What I am looking to achieve with this article is to expand on the great work that Honda-san has already done, and attempt to come up with a timeline as to which variants existed over which period of the production lifespan, and also add additional information regarding the other design evolutions.

Whilst we can learn from Honda-san’s vital and extensive research that a 43999 with a 5722A movement can exist, does that mean that anytime we see a 43999 with a 5722A movement inside, we can trust that the watch is correct?

Although this article is mainly intended as a guide to what to look for when purchasing one of these watches (as opposed to an in depth discussion a to the watch’s history), every now and then, I will also be including information from relevant historical publications.

I will structure this series of articles by the reference number of the watch as indicated on the caseback, first covering the steel cased watches, then the 18K gold, then cap gold, then the Toshiba commemorative pieces, and finally some rather fascinating outliers.

Grand Seiko 43999

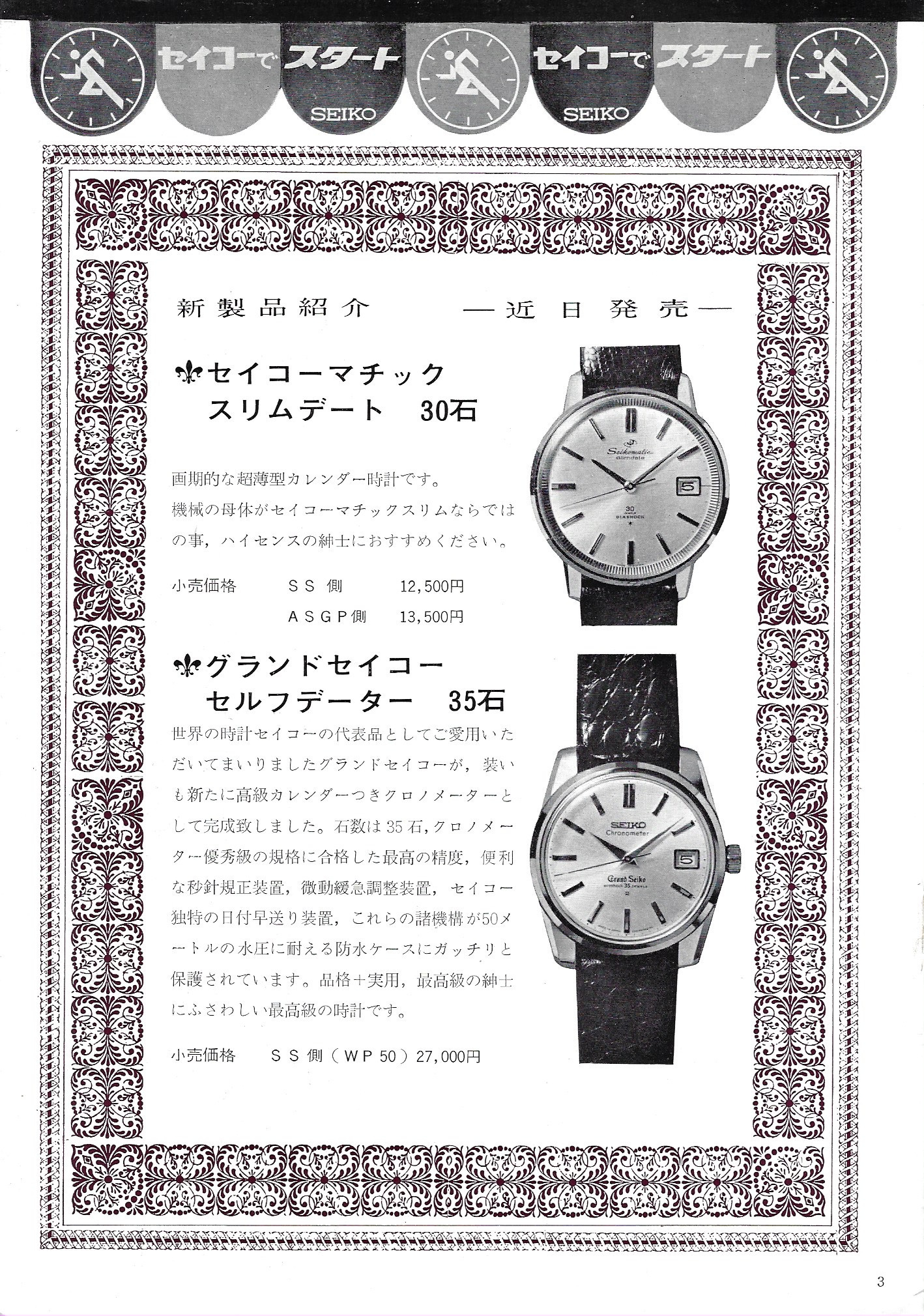

At the time of the launch of the Self Data, it was still two years before Seiko would commence publishing of their full annual/biannual catalogues, and so we have to hunt through other sources to find contemporary articles on the reference.

The earliest official Seiko publication that I have been able to track down that features the Self Dater is the February 1964 edition of Seiko News - the monthly publication sent out to Seiko authorised dealers to inform them of new product releases and other related company news.

The Japanese text in the above product announcement translates roughly as follows -

“Grand Seiko Self Dater 35 Jewels

The Grand Seiko, which has been used as a representative Seiko watch around the world, has now been given a new look as a luxury calendar chronometer. The number of jewels is 35; the highest precision that passes the chronometer standard; a convenient second hand control device; a fine adjustment device; a unique Seiko date fast advance device; and these mechanisms can withstand water pressure of 50m. It is fully protected by a waterproof case.

A top class watch that combines dignity and practicality, suitable for the finest gentelman.

Retail price - SS case (waterproof 50) 27,000 Yen”

Production timeline

The rationale for structuring this article around the watch reference number as found on the caseback, is that going hand in hand with that piece of data, is the caseback serial number, which provides us with the month and year of production. From there, we can then look at further details of the watch, such as the dial, movement, caseback medallion and crown.

Based on the examples seen (and from hereon in, assume that pretty much every “statement of fact” within this article should be assumed to be preceded by those words, although I will omit them going forward), the production of the 43999 commenced in August 1963, and finished in April 1965.

One interesting thing is that the production does not appear to be continuous - in other words, I have not seen examples of the 43999 produced in every month between the start and end of production. I will detail the months for which watches have been seen, in the hope that should any reader be aware of production outside these months, they will let me know so that I can improve the dataset.

Dial variants

Although I think it fair to say that usually people would only be considering a “matching” 43999 dial to be valid with a 43999 caseback, from an examination of the examples seen, it is clear to me that - as alluded to by Honda-san - a dial more usually associated with the next caseback to be looked into is also valid - but only within a certain timeframe.

43999 SD dial

The earliest production examples of the 43999 are undoubtedly the most highly sought after of all the steel cased 57GS series, and generally referred to as the “SD” dials. The SD designation (and associated compass symbol printed on the dial) indicate that the indices on the dial are made from a solid gold alloy, rather than simply gold plated. The lead photo in this article shows such a dial.

Given the interchangeability of the component parts of a 57GS series watch, it is not only likely, but in fact absolutely guaranteed, that over the years we will find examples of the “wrong” dial or the “wrong” movement being in the “wrong” case. The idea behind this article was to examine a sufficient number of watches to try to come up with a recommendation as to what could be considered “acceptable” based on the production date as inferred by the caseback serial number.

As such, any comments I make here should be considered my personal opinion on matters, and not an absolute and verifiable statement of fact. Whilst there are examples of SD dialed 43999s dated as late as September 1964 (well, one example), I would suggest that if you are in the market for an SD dialed 43999 to think very carefully before purchasing one that is dated later than January 1964.

43999 AD dial

Although referred to as the “AD” dial due to the star symbol on the dial indicating this, the actual dial code for this variant ends TD, and not AD.

Production of the AD dial variant would appear to have commenced in January 1964 (note that although I have seen two examples of AD dialed 43999’s from October 1963, I remain pretty convinced that these are both redialed, or recased movements), and continued through until April the following year. As we will see in due course, this dial is also found on two further caseback references.

Chronometer 5722-9990T AD dials

This may well come as a surprise to many, but I am pretty convinced now that it is perfectly acceptable to have a 43999 caseback with the later - what I refer to as the - 5722-9990T AD Chronometer dial as seen above.

Here is the caseback of the above watch, which sold on Yahoo in April 2019 -

The reason for this high level of confidence is that I have seen a number of examples of this configuration all dating from January 1965, a month that - as will become clear as this series of articles progress - can certainly be viewed as falling in a “transitional” period.

43999 caseback dial variant summary

Let’s now add a level of detail below the the production months for observed Grand Seiko 43999’s, and take a look at which months the dials hail from.

Outliers in this table I consider to be the AD dialed October 1963 production (one has a 5722A movement so I believe cannot possibly be correct); the SD dialed June and September 1964 production; and the October 1964 5722-9990T AD dialed production.

Movement variants

The vast majority of the 43999 casebacked 57GS that I have seen have the 430 movement. However, there appears to be a distinct cut off in December 1964, when we see the introduction of the 5722A movement. Interestingly, this is very close to when we see the “transitional” 43999’s with the Chronometer 5722-9990T AD dials in January 1965.

I discovered examples of two watches - one from August 1963 and one from October 1963 - that have the 5722A movement that I am absolutely convinced must be recased movements, or be watches that had their movement changed at service.

430 movements are seen very rarely - and sporadically - on later cases, but I will address those examples when they arise.

Note that the 430 and 5722A movements are - save for the engraving on the bridges - identical. The renaming was simply the result of Seiko’s move to a more standardized method of referencing their caliber families, and the movements within.

Finally for this section, a word on movement numbering.

Interestingly, there is a very strong correlation for the 430 and 5722A movements found in watches with 43999 casebacks between the first digit of the movement number, and the year of production as indicated by the case serial number.

A couple of things to note - there are gaps in the above table as there are instances where the seller shared a photo of the caseback of the watch, but not the movement. Additionally, we can now see that the single outlier watch in April 1965 with a 430 movement has a movement number starting with a 4. A very odd piece indeed!

There is just a single instance of a 430 movement that I have seen whose first number does not correlate with the year of production (give or take a month). This movement’s serial number is so strange that I simply cannot rationalise it. I very nearly purchased this one just for the oddity of it.

If you want to check out the auction for yourself (it was for a rather nice SD dialed watch with a case serial number indicating production in October 1963), you can find the listing here.

Combining the dial and movement data into a single table

Given that there are only two different movements, we can make an attempt to combine both movement and dial information into a single timeline. In the following table, the timeline of the three dial variants is plotted, colouring in the cells based on the movements found with those dials for the month in question.

Where a watch is found with the 430 movement, I will colour the cell red.

Where a watch is found with the 5722A movement, I will colour the cell yellow.

Should there be any months where both movements are found in the same dial, then the cell will be coloured orange, and I will comment after the table.

Makes perfect sense, no?

The red and yellow coloured cells are very clear to understand - there was a clear cut-off at some point during the month of December 1964 where the 5722A movement took over from the 430 movement, and it is obvious that the outlier here is the AD dialed 430 movement watch from April 1965.

That watch had a movement serial number starting 40, and it is worth highlighting that all other instances of 430 movements that have serial numbers starting 40 that I am aware of date from January 1964.

August 1963 is orange because there is a single instance of an SD dialed 5722A movement 43999 cased watch. This watch has to be a result of a movement change at service.

October 1963 has an orange cell because there are two AD dialed watches, one with a 5722A movement, and one with a 430 movement. In my view, both these watches are incorrect.

(There was no movement shot of the October 1964 Chronometer 5722-9990T AD dialed watch provided, so it cannot be included in this summary table.)

The executive summary if you are looking to purchase a Grand Seiko 43999 is actually very simple -

SD dialed watches should date from August 1963 through to January 1964. Yes, later examples have been seen, but you might find it a tough sell if you want to move the watch on at some point in the future. Only purchase if the watch has the 430 movement.

AD dialed watches dating from January 1964 through to November or December 1964 should have 430 movements. AD dialed watches dating from December 1964 or January 1965 onwards should have the 5722A movement.

Chronometer 5722-9990T AD dialed watches can be considered to be “true” transitional pieces, and multiple examples have been seen dating from January 1965, all with the 5722A movement.

Crowns

All 43999 cased watches should have the coarse-knurled crown, as seen pictured in the lead photo to this article.

Finally - something simple!

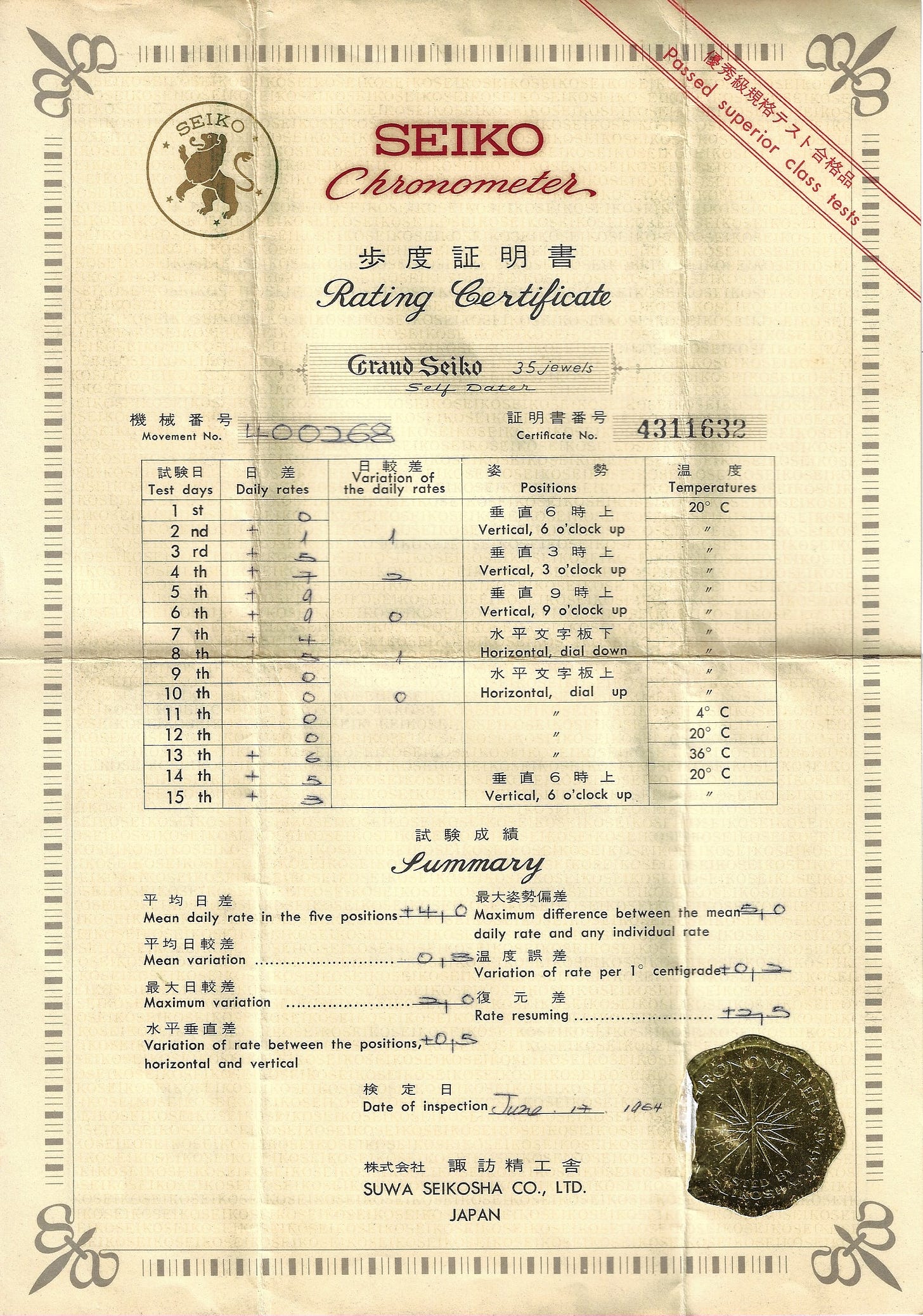

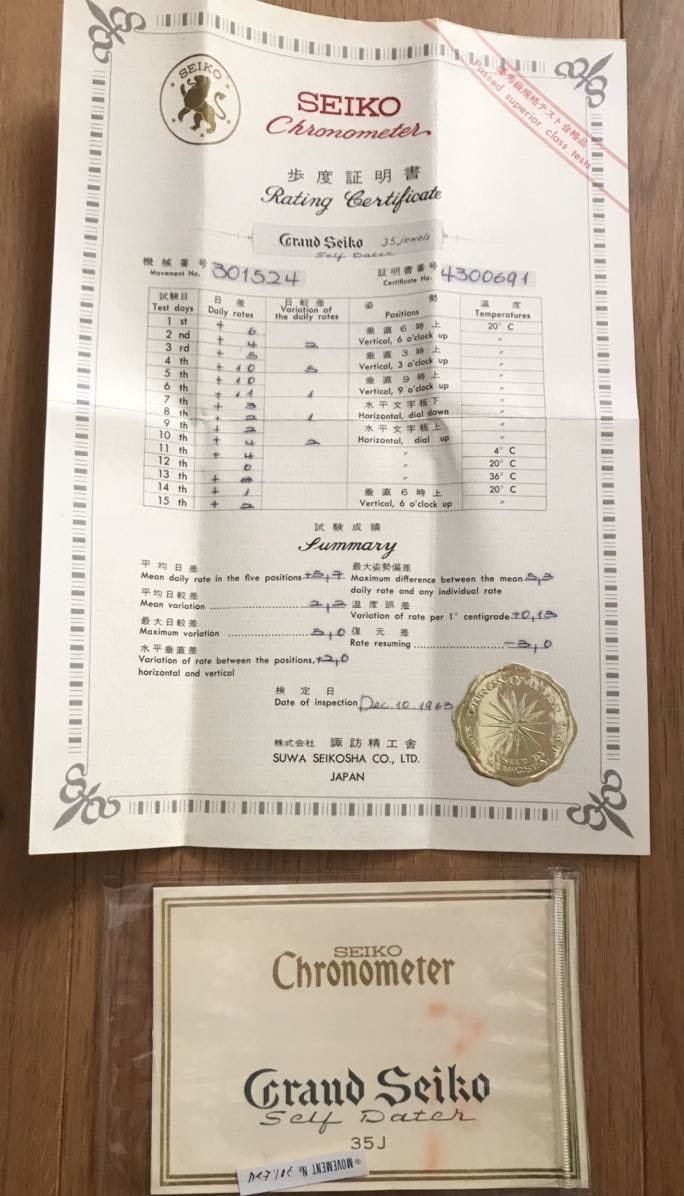

Certificates

At least three different certificates were used over the course of 57GS production. I say “at least three”, because I have a nagging suspicion I have actually seen a fourth variant, but can’t for the life of me track down a photo of it.

As mentioned earlier, finding a 57GS complete with its original certificate is extremely difficult indeed, and fewer than 10 examples have turned up on Yahoo Japan in the last decade.

For the 43999, it would seem almost certain that just the first two certificates were utilised, but it is not clear when the changeover was from the first to the second. As we will now find out, the early certificate is by far the more desirable one.

Here’s a scan -

43999 Certificate - early production

The reason why examples of the 43999 with the early type certificate are so desirable is because the certificate is - like those for the earlier first Grand Seiko - filled out by hand with the chronometry results of the movement being tested.

This certificate is so rare that the above is a scan of - if my memory serves me correctly - the only example I have ever seen accompanying its original watch (it’s from the full set pictured earlier).

Here’s the reverse side -

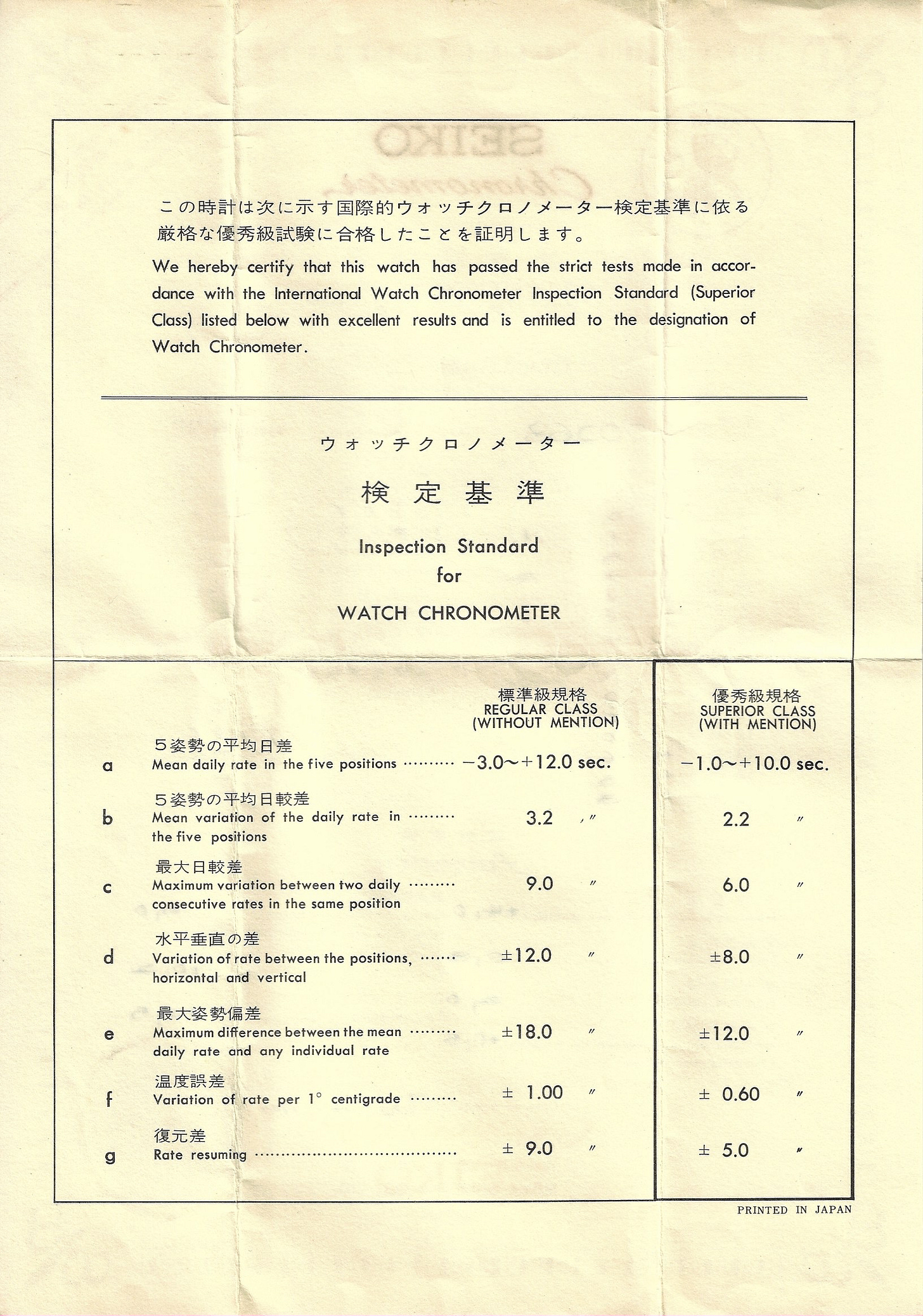

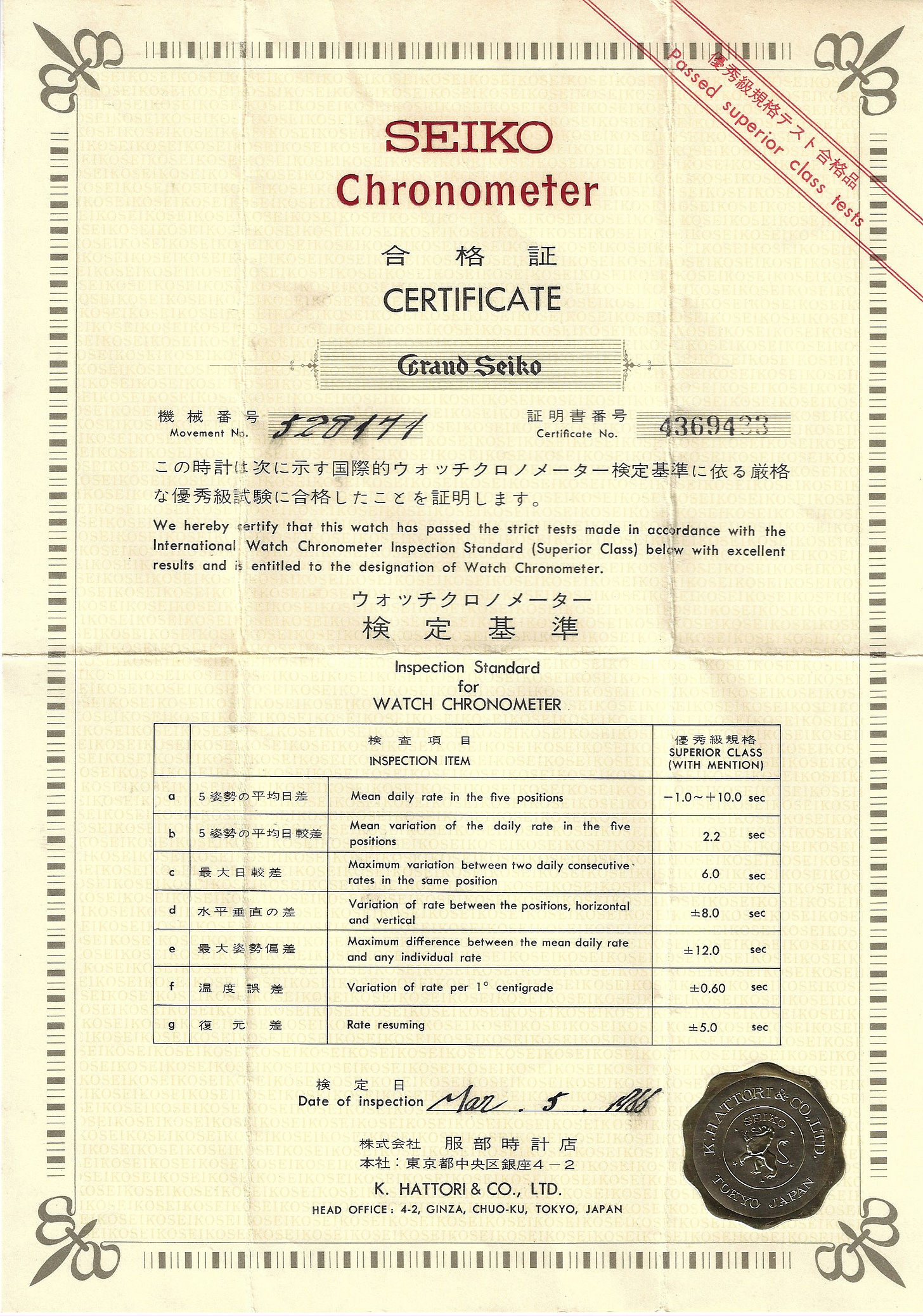

43999 Certificate - late production

Because certificates are so rare, we simply do not know exactly when Grand Seiko switched over from the earlier certificate seen above, to the later one that is shared below.

Given the earlier certificate is dated June 17th 1964, it is probably fair to assume that they were in use at least up until that date. However the crucial thing to stress is that the watch that certificate accompanies has a caseback serial number indicating production of the watch itself in January 1964 (note how this ties in with the very low numbered 4-series movement serial).

The earliest watch that I have seen with the later type certificate dates from September 1964, unfortunately however, that listing cannot be trusted 100% since the watch in question is the SD dialed variant mentioned earlier as an outlier. In addition, there is no photo provided of the movement, and both the movement number on the certificate and the certificate number have been somewhat digitally obfuscated (the former appears though to start 40, and the latter 43).

Here’s a photo from the listing -

What we can see however is that the certificate is dated October 25th 1964, so at least it is probably safe to assume this puts an absolute upper bound on possible dates for the early certificate.

The next earliest example that I have been able to track down of this certificate was in a listing accompanying an AD dialed 43999 dating from October 1964. Unfortunately we only see the certificate folded, but at least can infer from what we can see, that the movement number of the watch was 411234 -

The only example that I have been able to track down of the later type certificate accompanying the (assumed) correct 43999 AD dialed watch where the numbers are not withheld was in a rather interesting listing that I featured in one of the very early Friday newsletters that you can read here.

In the listing mentioned, a 43999 AD dialed watch dating from October 1964 was actually sold with two different certificates dated exactly one year apart.

Here’s the first certificate -

And it is immediately obvious from the date of the certificate and the movement serial number that this would have originally been issued with a 43999 SD dialed watch. We can also now deduce that the consistent 43 at the start of all the certificates we have seen so far implies they were issued for the 430 movements.

Unfortunately, when we take a look at the watch sold in that auction -

We can see that it’s actually an AD dialed example dating from October 1964.

The second certificate sold with the watch is more likely to match up, but without confirmation of the movement number of the watch itself, it is not possible to say for certain that it does. However, the fact that there is at least a swing tag with matching movement number to the certificate is very encouraging.

Although I don’t have a Grand Seiko 43999 with this later style certificate myself, I do have an example of the 5722-9990 dating from August 1965, when this style of certificate was still in use, so here’s a high resolution scan of that one -

As can be seen, this later style of certificate does not have any record of the actual chronometric performance of the movement tested - it merely states the standards that the movement needed to adhere to in order to pass certification as a Superior Class Chronometer.

OK that wraps it up for now. When I started writing this feature many hours ago (and after many dozens of hours spent compiling a database of every 57GS reference to have sold on Yahoo Japan in the last decade for over 100,000 yen!), I thought that I would write up the entire 57GS “primer” in a single article.

But, I think that it is actually best for me to split it up - both for my sanity, and yours!

The next installment will cover both the 5722-9990 and 5722-9991, and I hope to have it ready to publish by the end of the month.

![☆1 yen ~ [Good Condition] Grand Seiko Self Data Second Model 43999 Chronometer Cal.5722A Manual Winding Men's Watch [Rare]_1 ☆1 yen ~ [Good Condition] Grand Seiko Self Data Second Model 43999 Chronometer Cal.5722A Manual Winding Men's Watch [Rare]_1](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!geC3!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa8de86f0-dd79-4f0c-b9d6-aac698494b92_546x450.jpeg)

![☆1 yen ~ [Good Condition] Grand Seiko Self Data Second Model 43999 Chronometer Cal.5722A Manual Winding Men's Watch [Rare]_6 ☆1 yen ~ [Good Condition] Grand Seiko Self Data Second Model 43999 Chronometer Cal.5722A Manual Winding Men's Watch [Rare]_6](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!mlza!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc78d2541-5dd5-4d77-b592-38a22b4dc2af_525x450.jpeg)

Great, thank you so much! Any hope for the second part?

Great write up, thank you! I have a December 1964 AD 43999 with the 5722a purchased through yahoo auctions and I just love the watch. It’s the first vintage GS that grabbed me and it’s just so perfect.